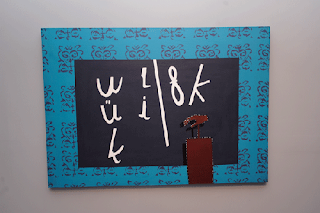

Translation II

IN A WORD

In this series, frieze d/e asks artists, curators or writers to reflect upon one word and its impact

My first serious intellectual split with my father – a devoted engineer in mind and soul – occurred after I told him that I had decided to do a degree in translation. For him, translation was an interesting but basically minor field; for me, it was the magic key to a wonderland where I could master the contexts of different languages and learn various vocabularies and their histories while becoming an active agent in communicating ideas from one side of a language divide to the other. During my studies, which were propelled by an almost obsessive interest in etymology, I was more drawn towards the processes of semiotics and, ironically, the issue of untranslatability.

The split I experienced with my father may be a symbol of the complex relationship with languages in Turkey, including Turkish itself. When Turkey was engineered as a republic in 1923, part of the revolution involved a complete change from Lisân-ı Osmânî (Ottoman, which was a balanced mixture of Turkish, Persian and Arabic, a translated language of translation) to a rationalized Turkish constructed with a Latin alphabet of 29 letters. We were taught in school that the change from the Arabic to the Latin script was necessary because Ottoman was too elaborate to be learnt and practiced by the common people. But the effect was to produce a violent cut from the imperial past and a trauma of collective imagination. Imagine how the transmission and translation of ideas is internally broken within the same landscape when you are not able to read newspapers published in your country 100 years ago. That’s why today, Turkish is a language rich in daily idioms and expressions with a strong literary tradition while it suffers from a lack of fluency in the intellectual terminology of concepts and ideas. And maybe that’s why part of the society – obsessed with engineering – realizes neither the value of multiple languages used in the country, such as Kurdish, Armenian and Greek, nor people’s right to be educated in their mother tongue alongside Turkish.

Rodchenko promoted the idea of the artist as an engineer who would constantly build the future. Translators ask a different question: What is lost and what is found when the imaginative and mental grammar is broken in this way? Recently, as my father reminded me of our split, I tried to explain the continuity that I see in my practice from translation to curating. The translator’s question provides me not only a tool for transformation but also a sensitive base to produce new critical positions to respond to the present day. He preferred not to continue this conversation. And I preferred to convey this experience here firstly in English – in this context, a neutral mirror which enabled me to process a critical distance in my relationship to my mother tongue.

—by Övül Durmuşoğlu